|

| 14-李鴻源 |

2008年6月27日

2008年6月25日

2008年6月15日

國際城市與水論壇會議 探討城市與水 各國專家提經驗 中國時報 2008.06.16

中國時報 2008.06.16

國際城市與水論壇會議 探討城市與水 各國專家提經驗

本報訊

一項大規模的國際城市與水論壇會議在台灣登場。第三屆國際城市論壇會議即將在十三、十四日在台北舉行,本次會議主題為「城市與水」,由IFoU國際城市論壇、台灣大學建築與城鄉研究所、臺北縣政府共同主辦。

台大城鄉所所長夏鑄九指出,本次會議邀集荷蘭、西班牙、義大利、日本、新加坡、韓國、中國大陸等歐亞地區國家之學者、專家,就各國案例探討城市與水的發展規畫經驗發表14場演說與座談。

##CONTINUE##

來自日本東京大學建築學院教授西村幸夫以日本滋賀縣近江八幡市說明日本的水與城市,他強調一個好的城市,一定會吸引觀光,但不能為觀光而觀光,必須避免避免過度旅遊開發,通過空間品質的提升,會變成優美環境,遊客就會來。

西村幸夫強調,近江八幡市就是藉由協商機制,透過工會、媒體宣傳,讓民眾參與,提升環境質量,當地居民發動了半日義務勞動,清除水草,清理環境,同時結合水與城市的發展,創造宜人居住的環境。

威尼斯Bernardo Secchi教授指出。水與城市發展關係密切,城市集中並非最好的發展模式,相對的城市分散佈置反而可能更具有鎃潛力。他說,威尼斯因為運河四通八達,所以城市就比較分散,但是他們將分散轉化成為優競爭勢,這樣一來當地民眾參與會比較容易,也因此創造新的城市發展模式,不是一味追求人口千萬城市發展。

荷蘭住房區域規畫環境部官員Henk Ovink也介紹荷蘭蘭得斯塔德區的發展計畫。他說,萊茵河三角洲大都市地區蘭得斯塔德區是一個包括阿姆斯特丹、鹿特丹、海牙及烏德斯勒四個多中心的城市群,每個城市人口不超過一百萬人,四就都市發展角度來看,並沒有競爭性,但四個城市加起來就有三百萬人,競爭性就強,因此他們規畫二○四○年空間區域發展規畫藍圖,讓它們成為有競爭力的城市,而四個大城市都有優勢定位,凸出各個城市特色,各個城市水有互補的效用。同時對於自然環境生態進行調查,改善交通系統,並對於全球暖化所帶來的氣候變遷及早提出因應對策。

這項論壇同時邀請北京毛其智教授主講「水系統與都市發展之北京案例」、上海鄭時齡教授主講「上海的水岸城市再生與都市轉化」、新加坡王財強教授主講「水與新加坡:從缺水到ABC」、香港鄒經宇教授「採生產管理之效能取向的可持續都市規畫與設計:以香港為例」、韓國韓武榮教授談「首爾的漢江復興計畫」以及台北縣副縣長李鴻源談「城市再活化:台北縣的經驗」。... Read more.

2008年6月12日

THE RIGHT TO THE CITY David Harvey

THE RIGHT TO THE CITY

David Harvey

(forthcoming: New Left Review)

“CHANGE THE WORLD” SAID MARX; “CHANGE LIFE” SAID RIMBAUD; FOR US, SAID ANDRE BRETTON, THESE TWO TASKS ARE ONE AND THE SAME - (A banner in the Plaza de Las Tres Culturas in the City of Mexico, site of the student massacre of 1968, January, 2008)

##CONTINUE##

We live in an era when ideals of human rights have moved center stage both politically and ethically. A lot of political energy is put into promoting, protecting and articulating their significance in the construction of a better world. For the most part the concepts circulating are individualistic and property-based and, as such, do nothing to challenge in any fundamental way hegemonic liberal and neoliberal market logics and neoliberal modes of legality and state action. We live in a world, after all, where the rights of private property and the profit rate trump all other notions of rights one can think of. But there are occasions when the ideal of human rights takes a collective turn, as when the rights of workers, women, gays and minorities come to the fore (a legacy of the long-standing labor movement and, for example, the 1960s Civil Rights movement in the United States that was collective and had a global resonance). Such struggles for collective rights have, on occasion, yielded important results (such that a woman and a black become real contestants for the US Presidency). I here want to explore another kind of collective right, that of the right to the city. This is apt at this historical moment because there is a revival of interest in Henri Lefebvre’s ideas on the topic as these were articulated forty years ago in relation to the movement of ’68, at the same time as there are various social movements around the world that are now demanding the right to the city as their goal. So what might the right to the city mean?

The city, as the noted urban sociologist Robert Park once wrote, is:

"man's most consistent and on the whole, his most successful attempt to remake the world he lives in more after his heart's desire. But, if the city is the world which man created, it is the world in which he is henceforth condemned to live. Thus, indirectly, and without any clear sense of the nature of his task, in making the city man has remade himself."1

If Park is correct, then the question of what kind of city we want cannot be divorced from the question of what kind of people we want to be, what kinds of social relations we seek, what relations to nature we cherish, what style of life we desire, what aesthetic values we hold. The right to the city is, therefore, far more than a right of individual access to the resources that the city embodies: it is a right to change the city more after our heart’s desire. It is, moreover, a collective rather than an individual right since changing the city inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power over the processes of urbanization. The freedom to make and remake ourselves and our cities is, I want to argue, one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights. How best then to exercise that right?

Since, as Park avers, we have hitherto lacked any clear sense of the nature of our task, it is useful first to reflect on how we have been made and re-made throughout history by an urban process impelled onwards by powerful social forces. The astonishing pace and scale of urbanization over the last hundred years means, for example, we have been re-made several times over without knowing why, how or wherefore. Has this dramatic urbanization contributed to human well-being? Has it made us into better people or left us dangling in a world of anomie and alienation, anger and frustration? Have we become mere monads tossed around in an urban sea? These were the sorts of questions that preoccupied all manner of nineteenth century commentators, such as Engels and Simmel, who offered perceptive critiques of the urban personas then emerging in response to rapid urbanization and in so doing suggested ways to change trajectories.2 These days it is not hard to enumerate all manner of urban discontents and anxieties as well as excitements in the midst of even more rapid urban transformations. Yet we somehow seem to lack the stomach for systematic critique. The maelstrom of change overwhelms us even as obvious questions loom. What, for example, are we to make of the immense concentrations of wealth, privilege and consumerism in almost all the cities of the world in the midst of what even the United Nations depicts as an exploding “planet of slums.”?3

To claim the right to the city in the sense I mean it here is to claim some kind of shaping power over the processes of urbanization, over the ways in which our cities are made and re-made and to do so in a fundamental and radical way. From their very inception, cities have arisen through the geographical and social concentration of a surplus product. Urbanization has always been, therefore, a class phenomenon of some sort, since surpluses have been extracted from somewhere and from somebody while the control over the disbursement of the surplus typically lies in a few hands (such as a religious oligarchy or a warrior poet with imperial ambitions). This general situation persists under capitalism, of course, but in this case there is a rather different dynamic at work. Capitalism rests, as Marx tells us, upon the perpetual search for surplus value (profit). This is what drives the capitalist dynamic. To produce surplus value, however, capitalists have to produce a surplus product. This means that capitalism is perpetually producing the necessary conditions for rapid urbanization. But then it turns out that the reverse relation also holds. Capitalism needs urbanization to absorb the surpluses it perpetually produces. In this way an inner connection emerges between the development of capitalism and urbanization. Hardly surprisingly, therefore, the logistical curves of growth of capitalist output over time are broadly paralleled by the logistical curves of urbanization of the world’s population.

Let us look more closely at what capitalists do. They begin the day with a certain amount of money and end the day with more of it (as profit). The next day they wake up and have to decide what to do with the surplus money they gained the day before. They face a Faustian dilemma: reinvest to get even more money or consume their surplus away in pleasures. The coercive laws of competition force them to reinvest because if one does not reinvest then another surely will. To remain a capitalist, some surplus must be reinvested to make even more surplus. Successful capitalists usually make more than enough surplus to reinvest in expansion and satisfy their lust for pleasure too. But the result of perpetual reinvestment is the expansion of surplus production at a compound rate - hence all the logistical growth curves (money, capital, output and population) that attach to the history of capital accumulation.

The politics of capitalism are affected by the perpetual need to find profitable terrains for capital surplus production and absorption. In this the capitalist faces a number of obstacles to continuous and trouble-free expansion. If there is a scarcity of labor and wages are too high then either existing labor has to be disciplined (technologically induced unemployment or an assault on organized working class power – such as that set in motion by Thatcher and Reagan in the 19980s - are two prime methods) or fresh labor forces must be found (by immigration, export of capital or proletarianization of hitherto independent elements in the population). New means of production in general and new natural resources in particular must be found. This puts increasing pressure on the natural environment to yield up the necessary raw materials and absorb the inevitable wastes. The coercive laws of competition also force new technologies and organizational forms to come on line all the time, since capitalists with higher productivity can out-compete those using inferior methods. Innovations define new wants and needs, reduce the turnover time of capital and the friction of distance. The latter extends the geographical range over which the capitalist is free to search for expanded labor supplies, raw materials, etc. If there is not enough purchasing power in the market then new markets must be found by expanding foreign trade, promoting new products and lifestyles, creating new credit instruments and debt-financed state expenditures. If, finally, the profit rate is too low, then state regulation of “ruinous competition,” monopolization (mergers and acquisitions) and capital exports to fresh pastures provide ways out.

If any one of the above barriers to continuous capital circulation and expansion becomes impossible to circumvent, then capital accumulation is blocked and capitalists face a crisis. Capital cannot be profitably re-invested, accumulation stagnates or ceases and capital is devalued (lost) and in some instances even physically destroyed. Devaluation can take a number of forms. Surplus commodities can be devalued or destroyed, productive capacity and the assets can be written down in value and left unemployed, or money itself can be devalued through inflation. And in a crisis, of course, labor stands to be devalued through massive unemployment. In what ways, then, has capitalist urbanization been driven by the need to circumvent these barriers and to expand the terrain of profitable capitalist activity? I here argue that it plays a particularly active role (along with other phenomenon such as military expenditures) in absorbing the surplus product that capitalists are perpetually producing in their search for surplus value and in providing new opportunities for the profitable investment of surplus capital in further expansion.4

Consider, first, the case of Second Empire Paris. The crisis of 1848 was one of the first clear crises of unemployed surplus capital and surplus labor side-by-side and it was European-wide. It struck particularly hard in Paris and the result was an abortive revolution on the part of unemployed workers and those bourgeois utopians who saw a social republic as the antidote to capitalist greed and inequality. The republican bourgeoisie violently repressed the revolutionaries but failed to resolve the crisis. The result was the ascent to power of Napoleon Bonaparte, who engineered a coup in 1851 and proclaimed himself Emperor in 1852. To survive politically, the authoritarian Emperor resorted to widespread political repression of alternative political movements but he also knew that he had to deal with the capital surplus problem and this he did by announcing a vast program of infrastructural investment both at home and abroad. Abroad this meant the construction of railroads throughout Europe and down into the Orient as well as support for grand works such as the Suez Canal. At home it meant consolidating the railway network, building ports and harbors, draining marshes, and the like. But above all it entailed the reconfiguration of the urban infrastructure of Paris. Bonaparte brought Haussmann to Paris to take charge of the public works in 1853.

Haussmann clearly understood that his mission was to help solve the surplus capital and unemployment problem by way of urbanization. The rebuilding of Paris absorbed huge quantities of labor and of capital by the standards of the time and, coupled with authoritarian suppression of the aspirations of the Parisian labor force, was a primary vehicle of social stabilization. Haussmann drew upon the utopian plans (by Fourierists and Saint-Simonians) for re-shaping Paris that had been debated in the 1840s, but with one big difference. He transformed the scale at which the urban process was imagined. When the architect Hittorf, showed Haussmann his plans for a new boulevard, Haussmann threw them back at him saying “not wide enough…you have it 40 meters wide and I want it 120.” Haussmann thought of the city on a grander scale, annexed the suburbs, redesigned whole neighborhoods (such as Les Halles) rather than just bits and pieces of the urban fabric. He changed the city wholesale rather than retail. To do this he needed new financial institutions and debt instruments which were constructed on Saint-Simonian lines (the Credit Mobilier and Immobiliere). What he did in effect was to help resolve the capital surplus disposal problem by setting up a Keynesian system of debt-financed infrastructural urban improvements. The system worked very well for some fifteen years and it entailed not only a transformation of urban infrastructures but the construction of a whole new urban way of life and the construction of a new kind of urban persona. Paris became “the city of light” the great center of consumption, tourism and pleasure - the cafés, the department stores, the fashion industry, the grand expositions all changed the urban way of life in ways that could absorb vast surpluses through crass consumerism (that offended traditionalists and excluded workers alike). But then the overextended and increasingly speculative financial system and credit structures on which this was based crashed in 1868. Haussmann was forced from power, Napoleon III in desperation went to war against Bismarck’s Germany and lost, and in the vacuum that followed arose the Paris Commune, one of the greatest revolutionary episodes in capitalist urban history. The Commune was wrought in part out of a nostalgia for the urban world that Haussmann had destroyed (shades of the 1848 revolution) and the desire to take back their city on the part of those dispossessed by Haussmann’s works. But the Commune also articulated conflictual forward looking visions of alternative socialist (as opposed to monopoly capitalist) modernities that pitted ideals of centralized hierarchical control (the Jacobin current) against decentralized anarchist visions of popular control (led by the Proudhonists). In 1872, in the midst of intense recriminations over who was at fault for the loss of the Commune, there occurred the radical political break between the Marxists and the Anarchists that to this day still unfortunately divides so much of the left opposition to capitalism.5

Fast forward now to 1942 in the United States. The capital surplus disposal problem that had seemed so intractable in the 1930s (and the unemployment that went with it) was temporarily resolved by the huge mobilization for the war effort. But everyone was fearful as to what would happen after the war. Politically the situation was dangerous. The Federal Government was in effect running a nationalized economy (and was doing so very efficiently) and the US was in alliance with the communist Soviet Union in the war against Fascism. Strong social movements with socialist inclinations had emerged in reponse to the depression of the 1930s and sympathizers were integrated into the war effort. We all know the subsequent history of the politics of McCarthyism and the Cold War (abundant signs of which were there in 1942). Like Louis Bonaparte, a hefty dose of political repression was evidently called for by the ruling classes of the time to reassert their power. But what of the capital surplus disposal problem?

In 1942 there appeared a lengthy evaluation of Haussmann’s efforts in an architectural journal. It documented in detail what he had done that was so compelling and attempted an analysis of his mistakes. The article was by none other than Robert Moses who after World War II did to the whole New York metropolitan region what Haussmann had done to Paris.6 That is, Moses changed the scale of thinking about the urban process and through the system of (debt-financed) highways and infrastructural transformations, through suburbanization and through the total re-engineering, not just of the city but of the whole metropolitan region, he defined a way to absorb the surplus product and thereby resolve the capital surplus absorption problem. This process, when taken nation-wide, as it was in all the major metropolitan centers of the United States (yet another transformation of scale), played a crucial role in the stabilization of global capitalism after World War II (this was a period when the US could afford to power the whole global non-communist economy through running trade deficits).

The suburbanization of the United States was not merely a matter of new infrastructures. As happened in Second Empire Paris, it entailed a radical transformation in lifestyles and produced a whole new way of life in which new products from suburban tract housing to refrigerators and air conditioners as well as two cars in the driveway and an enormous increase in the consumption of oil, all played their part in the absorption of the surplus. Suburbanization (alongside militarization) thus played a critical role in helping to absorb the surplus in the post-war years. But it did so at the cost of hollowing out the central cities and leaving them bereft of a sustainable economic basis, thus producing the so-called “urban crisis” of the 1960s, defined by revolts of impacted minorities (chiefly African-American) in the inner cities who were denied access to the new prosperity.

Not only were the central cities in revolt. Traditionalists increasingly rallied around Jane Jacobs and sought to counter the brutal modernism of Moses’ large scale projects with a different kind of urban aesthetic that focused on local neighborhood development, historical preservation and, ultimately, gentrification of older areas. But by then the suburbs had been built and the radical transformation in lifestyle that this betokened had all manner of social consequences, leading first wave feminists, for example, to proclaim the suburb and its lifestyle as the locus of all their primary discontents. As happened to Haussmann, a crisis began to unfold such that Moses fell from grace and his solutions came to be seen as inappropriate and unacceptable. And if the Haussmanization of Paris had a role in explaining the dynamics of the Paris Commune so the soulless qualities of suburban living played a critical role in the dramatic movements of 1968 in the USA, as discontented white middle class students went into a phase of revolt, seeking alliances with other marginalized groups and rallying against US imperialism to create a movement to build another kind of world including a different kind of urban experience (though again, anarchistic and libertarian currents were pitted against demands for hierachical and centralized alternatives). In Paris the movement to stop the left bank expressway and the invasion of central Paris and the destruction of traditional neighborhoods by the invading “high rise giants,” of which the Place d’Italie and the Tour Montparnasse were exemplary, likewise played an important role in animating the grander processes of the ’68 revolt. And it was in this context that Lefebvre wrote his prescient text in which he argued, among other things, not only that the urban process was crucial to the survival of capitalism and therefore bound to become a crucial focus of political and class struggle, but that this process was step by step obliterating the distinctions between town and country through the production of integrated spaces across the national space if not beyond.7 The 1960s in France was the decade when it became clear to Lefebvre that the peasantry as a quasi-independent rural social formation was threatened if not doomed by the industrialization and commercialization of agricultural production, a process that was to “go global” in the subsequent decades, aided by waves of technological innovation (such as the Green Revolution) and an insistence upon free trade. Large swaths of rural peasant populations all around the world were rendered bereft of the resources required to sustain life. The effect was to generate wave after wave of migrations of rural populations to form massive labor surpluses not only in the burgeoning cities of the south but also in the heart of the metropoles in the advanced capitalist world (where immigrants during these years were frequently welcomed and even sponsored by the state as a cheap source of labor supply, as with the Maghrebians in France and the Turks in Germany during the early 1970s). Under these conditions, Lefebvre argued that the right to the city had to mean the right to command the whole urban process that was increasingly dominating the countryside (everything from agribusiness to second homes and rural leisure and tourism). It was the production of space in general and of uneven geographical development and urbanization in particular that really mattered.

But along with the movement that produced the ‘68 revolt, which, as with the Commune, was part nostalgia for what had been lost and part forward-looking asking for the construction of a different kind of urban experience, went a financial crisis in the credit institutions that had powered the suburbanization process through debt-financing in the post-war period. This crisis gathered momentum at the end of the 1960s until the whole capitalist system crashed into a major global crisis, led by the bursting of the global property market bubble in 1973, followed by the fiscal bankruptcy of New York City in 1975. The dark days of the 1970s were upon us and, as had happened many times before, the question now was how to rescue capitalism from its own contradictions and in this, if history was to be any guide, the urban process was bound to play a significant role. The working through of the New York fiscal crisis of 1975, orchestrated by an uneasy alliance between state powers and financial institutions, pioneered the way towards the construction of a neoliberal ideological answer to the problems of perpetuation of class power (let the market do the work was the slogan). But how to revive the capacity to absorb the surpluses that capitalism must produce if it is to survive?8

Fast forward once again to our current conjuncture. International capitalism has been on a roller-coaster of regional crises and crashes (East and SouthEast Asia in 1997-8; Russia in 1998; Argentina in 2001, etc.) but has so far avoided a global crash even in the face of a chronic capital surplus disposal problem. What has been the role of urbanization in the stabilization of this situation? In the United States it is accepted wisdom that the housing market has been an important stabilizer of the economy, particularly since 2000 or so (after the high-tech crash of the late 1990s) although it was an active component of expansion during the 1990s. The property market has absorbed a great deal of the surplus capital directly through new construction (both inner city and suburban housing and new office spaces) while the rapid inflation of housing asset prices backed by a profligate wave of mortgage refinancing at historically low rates of interest boosted the U.S. internal market for consumer goods and services. The global market has in part been stabilized through US urban expansion as the U.S. runs huge trade deficits with the rest of the world, borrowing around $2 billion a day to fuel its insatiable consumerism and the debt financed war in Afghanistan and Iraq.

But the urban process has undergone another transformation of scale. It has, in short, gone global. So we cannot focus merely on the United States. Similar property market booms in Britain and Spain, as well as in many other countries, have helped power the capitalist dynamic in ways that have broadly paralleled what has happened in the United States. The urbanization of China over the last twenty years has been of a different character (with its heavy focus on building infrastructures), but even more important than that of the USA. Its pace picked up enormously after a brief recession in 1997 or so, such that China has absorbed nearly half of the world’s cement supplies since 2000. More than a hundred cities have passed the one million population mark in the last twenty years and small villages, like Shenzhen, have become huge metropolises with 6 to 10 million people. Industrialization, at first concentrated in the special economic zones, but then rapidly diffused outwards to any municipality willing to absorb the surplus capital from abroad and plough back the earnings into rapid expansion. Vast infrastructural projects, such as dams and highways – again, all debt financed – are transforming the landscape.9 Equally vast shopping malls, science parks, airports, container ports, pleasure palaces of all kinds, and all manner of newly-minted cultural institutions along with gated communities and golf courses dot the Chinese landscape in the midst of overcrowded urban dormitories for the massive labor reserves being mobilized and intense poverty in the rural regions that supply the migrant labor. The consequences of this urbanization process for the global economy and for the absorption of surplus capital have been significant: Chile booms because of the demand for copper, Australia thrives and even Brazil and Argentina recover in part because of the strength of demand from China for raw materials. Is the urbanization of China the primary stabilizer of global capitalism? The answer has to be a partial yes. But China is only the epicenter for an urbanization process that has now become genuinely global in part through the astonishing global integration of financial markets that use their flexibility to debt-finance urban projects from Dubai to Sao Paulo and from Madrid and Mumbai to Hong Kong and London. The Chinese central bank, for example, has been active in the secondary mortgage market in the USA while Goldman Sachs has been heavily involved in the surging property market in Mumbai and Hong Kong capital has invested in Baltimore. Every urban area in the world has its building boom in full swing in the midst of a flood of impoverished migrants that is simultaneously creating a planet of slums, the end-game for a dispossessed rural peasantry that step-by step is being willingly or unwillingly integrated into the urban process, as the industrialization and commercialization of agricultural production, that began in the 1960s, completes its domination of rural life.

The building booms are evident in Mexico City, Santiago in Chile, in Mumbai, Johannesburg, Seoul, Taipei, Moscow, and all over Europe (Spain being most dramatic) as well as in the cities of the core capitalist countries such as London, Los Angeles, San Diego and New York (where more large-scale urban projects are now in motion under the billionaire Bloomberg’s administration than ever before). Astonishing, spectacular and in some respects criminally absurd urbanization projects have emerged in the Middle East in places like Dubai and Abu Dhabi as a way of mopping up the capital surpluses arising from oil wealth in the most conspicuous, socially unjust and environmentally wasteful ways possible (like an indoor ski slope in a hot desert environment). We are here looking at yet another transformation in scale of the urban process, one that makes it hard to grasp that what may be going on globally is in principle similar to the processes that Haussmann managed so expertly for a while in Second Empire Paris.

This urbanization boom has depended, however, as did all the others before it, on the construction of new financial institutions and arrangements to organize the credit required to sustain it. Financial innovations set in train in the 1980s, particularly the securitization and packaging of local mortgages for sale to investors world-wide, and the setting up of new financial institutions to facilitate a secondary mortgage market and to hold collateralized debt obligations, has played a crucial role. The benefits of this were legion: it spread risk and permitted surplus savings pools easier access to surplus housing demand and it also, by virtue of its coordinations, brought aggregate interest rates down (while generating immense fortunes for the financial intermediaries who worked these wonders). But spreading risk does not eliminate risk. Furthermore, the fact that risk can be spread so widely encourages even riskier local behaviors because the risk can be transferred elsewhere. Without adequate risk assessment controls, the mortgage market got out of hand and what happened to the Pereire Brothers in 1867-8 and to the fiscal profligacy of New York City in the early 1970s, has now turned into a so-called sub-prime mortgage and housing asset-value crisis. The crisis is concentrated in the first instance in and around US cities (though similar signs can be seen in Britain) with particularly serious implications for low-income African Americans and single head-of-household women in the inner cities. It also affects those who, unable to afford the sky-rocketing housing prices in the urban centers, particularly in the US Southwest, moved to the semi-periphery of metropolitan areas to take up speculatively built tract housing at initially easy credit rates but who now face escalating commuting costs with rising oil prices and soaring mortgage payments as market-interest rates kick in. This crisis, with vicious local impacts on urban life and infrastructures (whole neighborhoods in cities like Cleveland,Baltimore and San Diego have been devastated by the foreclosure wave), also threatens the whole architecture of the global financial system and may trigger a major recession to boot. The parallels with the 1970s are, to put it mildly, uncanny (including the immediate easy-money response of the US Federal Reserve, which is almost certain to generate strong currents of uncontrollable inflation if not stagflation, as happened in the 1970s, in the not too distant future).

But the situation is far more complex now and it is an open question as to whether a serious crash in the United States can be compensated for elsewhere (e.g. by China, although even here the pace of urbanization seems to be slowing down). Uneven geographical development may once again rescue (as it did in the 1990s) the system from a totalizing global crash, though it is the US that is this time at the center of the problem. But the financial system is also much more tightly coupled temporally than it ever was before.10 Computer-driven split-second trading, once it does go off track, always threatens to create some great divergence in the market (it is already producing incredible volatility in stock markets) that will produce a massive crisis requiring a total re-think of how finance capital and money markets work, including in relation to urbanization processes.

As in all the preceding phases, this most recent radical expansion of the urban process has brought with it incredible transformations of lifestyle. Quality of urban life has become a commodity for those with money, as has the city itself in a world where consumerism, tourism, cultural and knowledge-based industries as well as perpetual resort to the economy of the spectacle, have become major aspects of urban political economy, even in India and China. The postmodernist penchant for encouraging the formation of market niches, both in urban lifestyle choices and in consumer habits, and cultural forms, surrounds the contemporary urban experience with an aura of freedom of choice in the market, provided you have the money and can protect yourself from the privatization of wealth redistribution through burgeoning criminal activity. Shopping malls, multiplexes and box stores proliferate (the production of each has become big business) as do fast food and artisanal market places, boutique cultures and, as Sharon Zukin slyly notes, “pacification by cappuccino.” Even the incoherent, bland and monotonous suburban tract development that continues to dominate in many areas, now gets its antidote in a “new urbanism” movement that touts the sale of community and a boutique lifestyle as a developer product to fulfill urban dreams. This is a world in which the neoliberal ethic of intense possessive individualism can become the template for human personality socialization. The impact is increasing individualistic isolation, anxiety and neurosis in the midst of one of the greatest social achievements (at least judging by its enormity and all-embracing character) ever constructed in human history for the realization of our heart’s desire.

But the fissures within the system are also all too evident. We increasingly live in divided, fragmented and conflict-prone cities. How we view the world and define possibilities depends on which side of the tracks we are on and to what kinds of consumerism we have access to. In the past decades, the neoliberal turn has restored class power to rich elites.11 In a single year one hedge fund manager in New York raked in $1.7 billion in personal remuneration and Wall Street bonuses have soared for individuals over the last few years from around $5 million towards the $50 million mark for top players (putting real estate prices in Manhattan out of sight). Fourteen billionaires have emerged in Mexico since the neoliberal turn in the late 1980s and Mexico now boasts the richest man on earth, Carlos Slim, at the same time as the incomes of the poor in that country have either stagnated or diminished. The results of this increasing polarization in the distribution of wealth and power are indelibly etched into the spatial forms of our cities, which increasingly become cities of fortified fragments, of gated communities and privatized public spaces kept under constant surveillance. The neoliberal protection of private property rights and their values becomes a hegemonic form of politics, even for the lower middle class, In the developing world in particular, the city:

“is splitting into different separated parts, with the apparent formation of many “microstates.” Wealthy neighborhoods provided with all kinds of services, such as exclusive schools, golf courses, tennis courts and private police patrolling the area around the clock intertwine with illegal settlements where water is available only at public fountains, no sanitation system exists, electricity is pirated by a privileged few, the roads become mud streams whenever it rains, and where house-sharing is the norm. Each fragment appears to live and function autonomously, sticking firmly to what it has been able to grab in the daily fight for survival.”12

Under these conditions, ideals of urban identity, citizenship and belonging, of a coherent urban plitics, already threatened by the spreading malaise of the individualistic neoliberal ethic, become much harder to sustain. Even the idea that the city might function as a collective body politic, a site within and from which progressive social movements might emanate, appears increasingly implausible. Yet there are in fact all manner of urban social movements in evidence seeking to overcome the isolations and to re-shape the city in a different social image to that given by the powers of developers backed by finance, corporate capital, and an increasingly entrepreneurially minded local state apparatus. Even relatively conservative urban administrations are seeking ways to use their powers to experiment with new ways of both producing the urban and of democratizing governance. Is there an urban alternative and, if so, from whence might it come?

But surplus absorption through urban transformation has an even darker aspect. It has entailed repeated bouts of urban restructuring through “creative destruction.”

This nearly always has a class dimension since it is usually the poor, the underprivileged and those marginalized from political power that suffer first and foremost from this process. Violence is required to achieve the new urban world on the wreckage of the old. Haussmann tore through the old Parisian slums, using powers of expropriation for supposedly public benefit and did so in the name of civic improvement, environmental restoration and urban renovation. He deliberately engineered the removal of much of the working class and other unruly elements along with insalubrious industries, from Paris’s city center where they constituted a threat to public order, public health and, of course, political power. He created an urban form where it was believed (incorrectly as it turned out in 1871) sufficient levels of surveillance and military control were possible so as to ensure that revolutionary movements could easily be controlled by military power. But, as Engels pointed out in 1872:

“In reality, the bourgeoisie has only one method of solving the housing question after its fashion – that is to say, of solving it in such a way that the solution perpetually renews the question anew. This method is called ‘Haussmann’ (by which) I mean the practice that has now become general of making breaches in the working class quarters of our big towns, and particularly in areas which are centrally situated, quite apart from whether this is done from considerations of public health or for beautifying the town, or owing to the demand for big centrally situated business premises, or, owing to traffic requirements, such as the laying down of railways, streets (which sometimes seem to have the aim of making barricade fighting more difficult)….No matter how different the reasons may be, the result is always the same; the scandalous alleys disappear to the accompaniment of lavish self-praise by the bourgeoisie on account of this tremendous success, but they appear again immediately somewhere else…..The breeding places of disease, the infamous holes and cellars in which the capitalist mode of production confines our workers night after night, are not abolished; they are merely shifted elsewhere! The same economic necessity that produced them in the first place, produces them in the next place.” 13

Actually it took more than a hundred years to complete the embourgeoisment of central Paris with the consequences that we have seen in recent years of uprisings and mayhem in those isolated suburbs within which the marginalized immigrants and the unemployed workers and youth are increasingly trapped. The sad point here, of course, is that the processes Engels described recur again and again in capitalist urban history. Robert Moses “took a meat axe to the Bronx” (in his infamous words) and long and loud were the lamentations of neighborhood groups and movements, that eventually coalesced around the rhetoric of Jane Jacobs, at both the unimaginable destruction of valued urban fabric but also of whole communities of residents and their long-established networks of social integration.14 But in the New York and Parisian case, once the brutal power of state expropriations had been successfully resisted and contained by the agitations of ‘68, a far more insidious and cancerous process of transformation occurred through fiscal disciplining of democratic urban governments, land markets, property speculation and the sorting of land to those uses that generated the highest possible financial rate of return under the land’s “highest and best use.” Engels understood all too well what this process was about too:

“The growth of the big modern cities gives the land in certain areas, particularly in those areas which are centrally situated, an artificially and colossally increasing value; the buildings erected on these areas depress this value instead of increasing it, because they no longer belong to the changed circumstances. They are pulled down and replaced by others. This takes place above all with worker’s houses which are situated centrally and whose rents, even with the greatest overcrowding, can never, or only very slowly, increase above a certain maximum. They are pulled down and in their stead shops, warehouses and public building are erected.”15

It is depressing to think that all of this was written in 1872, for Engels’ description applies directly to contemporary urban processes in much of Asia (Delhi, Seoul, Mumbai) as well as to the contemporary gentrification of, say, Harlem and Brooklyn in New York. A process of displacement and dispossession, in short, also lies at the core of the urban process under capitalism. This is the mirror image of capital absorption through urban redevelopment. Consider the case of Mumbai where there are 6 million people considered officially as slum dwellers settled on the land for most part without legal title (the places they live are left blank on all maps of the city). With the attempt to turn Mumbai into a global financial center to rival Shanghai, the property development boom gathers pace and the land the slum dwellers occupy appears increasingly valuable. The value of the land in Dharavi, one of the most prominent slums in Mumbai, is put at $2 billion and the pressure to clear the slum (for environmental and social reasons that mask the land grab) is mounting daily. Financial powers backed by the state push for forcible slum clearance, in some cases violently taking possession of a terrain occupied for a whole generation by the slum dwellers. Capital accumulation on the land through real estate activity booms as land is acquired at almost no cost. Do the people forced out get compensation? The lucky ones get a bit. But while the Indian constitution specifies that the state has the obligation to protect the lives and well-being of the whole population irrespective of caste and class, and to guarantee rights to livelihood housing and shelter, the Indian Supreme Court has issued both non-judgments and judgments that re-write this constitutional requirement. Since the slum dwellers are illegal occupants and many cannot definitively prove their long-term residence on the land, they have no right to compensation. To concede that right, says the Supreme Court, would be tantamount to rewarding pickpockets for their actions. So the slum-dwellers either resist and fight or move with their few belongings to camp out on the highway margins or wherever they can find a tiny space.16 Similar examples of dispossession (though less brutal and more legalistic) can be found in the United States through the abuse of rights of eminent domain to displace long-term residents in reasonable housing in favor of higher order land uses (such as condominiums and box stores). Challenged in the U.S. Supreme Court, the liberal justices carried the day against the conservatives in saying it was perfectly constitutional for local jurisdictions to behave in this way in order to increase their property tax base.

In Seoul in the 1990s, the construction companies and developers hired goon squads of sumo wrestler types to invade whole neighborhoods and smash down with sledgehammers not only the housing but also all the possessions of those who had built their own housing on the hillsides of the city in the 1950s on what had become by the 1990s high value land. Most of those hillsides are now covered with high-rise towers that show no trace of the brutal processes of land clearance that permitted their construction. In China millions are being dispossessed of the spaces they have long occupied. Lacking private property rights, the state can simply remove them from the land by fiat offering a minor cash payment to help them on their way (before turning the land over to developers at a high rate of profit). In some instances people move willingly but widespread resistances are also reported, the usual response to which is brutal repression by the Communist party. In the Chinese case it is often populations on the rural margins who are displaced illustrating the significance of Lefebvre’s argument, presciently laid out in the 1960s, that the clear distinction that once existed between the urban and the rural was gradually fading into a set of porous spaces of uneven geographical development under the hegemonic command of capital and the state. This is the case also in India, where the special economic development zones policy now favored by central and state governments is leading to violence against agricultural producers, the grossest of which was the massacre at Nandigram in West Bengal, orchestrated by the ruling Marxist political party, to make way for large scale Indonesian capital that is as much interested in urban property development as it is in industrial development. Private property rights in this case provided no protection. And so it is with the seemingly progressive proposal of awarding private property rights to squatter populations in order to offer them the assets that will permit them to emerge out of poverty. This is the sort of proposal now mooted for Rio’s favelas, but the problem is that the poor, beset with insecurity of income and frequent financial difficulties, can easily be persuaded to trade in that asset for a cash payment at a relatively low price (the rich typically refuse to give up their valued assets at any price which is why Moses could take a meat axe to the low-income Bronx but not to affluent Park Avenue). My bet is that, if present trends continue, within fifteen years all those hillsides now occupied by favelas will be covered by high-rise condominiums with fabulous views over Rio’s bay while the erstwhile favela dwellers will have been filtered off to live in some remote periphery.17 The long-term effect of Margaret Thatcher’s privatization of social housing in central London has been to create a rent and housing price structure throughout the metropolitan area that precludes lower income and now even middle class people having access to housing anywhere near the urban center. The housing problem as well as the poverty and accessibility problem has indeed been moved around.

These examples warn of us the existence of a whole battery of seemingly “progressive” solutions that not only move the problem around but actually strengthen while simultaneously lengthening the golden chain that imprisons vulnerable and marginalized populations within orbits of capital circulation and accumulation. Hernan de Soto influentially argues that it is the lack of clear property rights that holds the poor down in misery in so much of the global south (ignoring the fact that poverty is abundantly in evidence in societies where clear property rights are readily established). To be sure, there will be instances where the granting of such rights in Rio’s favelas or in Lima’s slums, liberates individual energies and entrepreneurial endeavors leading to personal advancement. But the concomitant effect is often to destroy collective and non profit-maximizing modes of social solidarity and mutual support, while any aggregate effect will almost certainly be nullified in the absence of secure and adequately remunerative employment. In Cairo, Elyachar, for example, notes how these seemingly progressive policies create a “market of dispossession” that in effect seeks to suck value out of a moral economy based on mutual respect and reciprocity to the advantage of capitalist institutions.

Much the same commentary applies to the micro-credit and micro-finance solutions to global poverty now touted so persuasively among the Washington financial institutions. Micro-credit in its social incarnation (as originally envisaged by the Nobel Peace Prize winner, Yunnus) has indeed opened up new possibilities and had a significant impact on gender relations with positive consequences for women in countries such as India and Bangladesh. But it does so by imposing systems of collective responsibility for debt repayments that can imprison rather than liberate. In the world of micro-finance as articulated by the Washington institutions (as opposed to the social and more philanthropic orientation of micro-credit proposed by Yunnus) the effect is to generate high-yielding sources of income (at least 18% rate of interest and often far higher) for global financial institutions in the midst of an emergent marketing structure that permits multinational corporations access to the massive aggregate market constituted by the 2 billion people living on less that $2 a day. This huge “market at the bottom of the pyramid” as it is called in business circles, is to be penetrated on behalf of big business by constructing elaborate networks of salespeople (chiefly women) linked through a marketing chain from multinational warehouse to street vendors. The sales people form a collective of social relations, all responsible for each other, set up for guaranteeing repayment of the debt plus interest that allows them to buy the commodities that they subsequently market piecemeal. As with granting private property rights, almost certainly some people (and in this case mostly women) may and even go on to become relatively well off while notorious problems of difficulty of access of the poor to consumer products at reasonable prices will be attenuated. But this is no solution to the urbanimpacted poverty problem. Most participants in the micro-finance system will be reduced to the status of debt peonage, locked into a badly-remunerated bridge position between the multinational corporations and the impoverished populations of the urban slums, with the advantage always going to the multinational corporation. This is the kind of structure that will block the exploration of more productive alternatives. It certainly does not proffer any right to the city.

Urbanization we may conclude has played a crucial role in the absorption of capital surpluses and has done so at every increasing geographical scales but at the price of burgeoning processes of creative destruction that entail the dispossession of the urban masses of any right to the city whatsoever. Periodically this ends in revolt, as the dispossessed in Paris rose up in 1871, seeking to reclaim the city they had lost. The urban social movements of 1968, from Paris and Bangkok to Mexico City and Chicago, likewise sought to define a different way of urban living from that which was being imposed upon them by capitalist developers and the state. If, as seems likely, the fiscal difficulties in the current conjuncture mount and the hitherto successful neoliberal, postmodernist and consumerist phase of capitalist absorption of the surplus through urbanization is at an end and a broader crisis ensues, then the question arises: where is our ’68 or, even more dramatically, our version of the Commune?

By analogy with transformations in the fiscal system, the political answer is bound to be much more complex in our times precisely because the urban process is now global in scope and wracked with all manner of fissures, insecurities and uneven geographical developments. But cracks in the system are, as Leonard Cohen once sang, “what lets the light in.” Signs of revolt are everywhere (the unrest in China and India is chronic, civil wars rage in Africa, Latin America is in ferment, autonomy movements are emerging all over the place, and even in the United States the political signs suggest that most of the population is saying “enough is enough” with respect to the rabid inequalities). Any of these revolts could suddenly become contagious. Unlike the fiscal system, however, the urban and peri-urban social movements of opposition, of which there are many around the world, are not tightly coupled at all. Indeed many have no connection to each other. It is unlikely, therefore, that a single spark will, as the Weather Underground once dreamed, spark a prairie fire. It will take something far more systematic than that. But if these various oppositional movements did somehow come together, coalesce, for example, around the slogan of the right to the city, then what should they demand?

The answer to the last question is simple enough: greater democratic control over the production and use of the surplus. Since the urban process is a major channel of use, then the right to the city is constituted by establishing democratic control over the deployment of the surpluses through urbanization. To have a surplus product is not a bad thing: indeed, in many situations a surplus is crucial to adequate survival. Throughout capitalist history, some of the surplus value created has been taxed away by the state and in social democratic phases that proportion rose significantly putting much of the surplus under state control. The whole neoliberal project over the last thirty years has been oriented towards privatization of control over the surplus. The data for all OECD countries show, however, that the share of gross output taken by the state has been roughly constant since the 1970s. The main achievement of the neoliberal assault, then, has been to prevent the state share expanding in the way it was in the 1960s. One further response has been to create new systems of governance that integrate state and corporate interests and, through the application of money power, assure that control over the disbursement of the surplus through the state apparatus favors corporate capital and the upper classes in the shaping of the urban process. Increasing the share of the surplus under state control will only work if the state itself is both reformed and brought back under popular democratic control.

Increasingly, we see the right to the city falling into the hands of private or quasi-private interests. In New York City, for example, we have a billionaire mayor, Michael Bloomberg, who is re-shaping the city along lines favorable to the developers, to Wall Street and transnational capitalist class elements, while continuing to sell the city as an optimal location for high value businesses and a fantastic destination for tourists, thus turning Manhattan in effect into one vast gated community for the rich. In Seattle, a billionaire like Paul Allen calls the shots and in Mexico City the wealthiest man in the world, Carlos Slim, has the downtown streets re-cobbled to suit the tourist gaze. And it is not only affluent individuals that exercise direct power. In the town of New Haven, strapped for any resources for urban reinvestment of its own, it is Yale University, one of the wealthiest universities in the world, that is redesigning much of the urban fabric to suit its needs. Johns Hopkins is doing the same for East Baltimore and Columbia University plans to do so for areas of New York (sparking neighborhood resistance movements in both cases, as has the attempted land grab in Dharavi). The actually ecxisting right to the city, as it is now constituted, is far too narrowly confined, in most cases in the hands of a small political and economic elite who are in the position to shape the city more and more after then own particular heart’s desire.

But let us look at this situation more structurally. In January every year an estimate is published of the total of Wall Street bonuses earned for all the hard work the financiers engaged in the previous year. In 2007, a disastrous year for financial markets by any measure, the bonuses added up to $33.2 billion, only 2 per cent less than the year before (not a bad rate of remuneration for messing up the world’s financial system). In mid-summer of 2007, the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank pumped billions of short-term credit into the financial system to ensure its stability and the Federal Reserve dramatically lowered interest rates as the year progressed every time the Wall Street markets threatened to fall precipitously. Meanwhile, some two perhaps three million people, mainly women single headed households and African Americans in central cities and marginalized white populations in the urban semi-periphery, have been or are about to be rendered homeless by foreclosures, Many city neighborhoods and even whole peri-urban communities in the US, have been boarded up and vandalized, wrecked by the predatory lending practices of the financial institutions. This population is due no bonuses. Indeed, since foreclosure means forgiveness of debt and that is regarded as income, many of those foreclosed face a hefty income tax bill for money they never had in their possession. This awful asymmetry poses the following question: why could not the Federal Reserve extend medium-term liquidity help to the households threatened with foreclosure to until mortgage restructuring at reasonable rates could resolve much of the problem? The ferocity of the credit crisis would have been mitigated and impoverished people and the neighborhoods they inhabited would have been protected. Furthermore, the global financial system would not have teetered on the brink of insolvency. To be sure, this would extend the mission of the Federal Reserve beyond its normal remit and go against the neoliberal ideological rulee that in the event of a conflict between the well-being of financial institutions and that of the people, then the people should be left to one side, to say nothing of class preferences with respect to income distribution and notions of personal responsibility. But just look at the price we are paying for the observing of such rules and the senseless creative destruction that goes along with it? Surely something can and should be done to reverse this process?

We have, however, yet to see a coherent oppositional movement to all of this in the twenty-first century. There is, of course, a multitude of diverse urban struggles and urban social movements (in the broadest sense of that term to include movements in the rural hinterlands) already in existence. Urban innovations with respect to environmental sustainability, cultural incorporation of immigrants, and urban design of public housing spaces are observable around the world in abundance. But they have yet to converge on the singular aim of gaining greater control over the uses of the surplus (let alone over the conditions of its production). One step, though by no means final, towards unification of these struggles is to laser in on those moments of creative destruction where the economy of wealth accumulation collides violently with the economy of dispossession and there proclaim on behalf of the dispossessed their right to the city, their right to both change the world and change life. That collective right, as both a working slogan and a political ideal, brings us back to the age-old question as to who it is that commands the inner connection between urbanization and surplus production and use. Perhaps, after all, Lefebvre was right some forty years ago, to insist that the revolution in our times has to be urban - or nothing.... Read more.

2008年6月11日

會議主旨

6/13 Day 1 議程

Morning session: Moderator Prof. Hsia Chu-Joe

上午場次:主持人夏鑄九教授

09:00 - 09:30 Reception 簽到

09:30 – 09:45

Welcome and openingMr. Chou Hiswei(Governer of Taipei County

Government)Prof. Hsia Chu-Joe (Director of Graduate Institute of Building

and Planning, Taiwan University)

開幕式周縣長錫瑋致詞、夏鑄九教授致詞

09:45 – 10:00

Prof. Jürgen RosemannIntroduction of the theme

“City and Water” 講者:Jürgen Rosemann教授-研討會主題介紹:城市與水

10:00 – 10:45

Keynote Speech

Prof. Nishimura Yukio-Water and City in Japan: The Case on Omi-Hachiman City,

Shiga Prefecture

講者:西村幸夫教授

講題:日本的水與城市:日本滋賀縣近江八幡市案例

##CONTINUE##

10:45 – 11:15 Coffee break休息

11:15 – 12:00

Keynote SpeechProf.

Bernardo Secchi-Cities and water: some European case studies

講者:Bernardo Secchi教授

講題:水與城市:歐洲案例介紹

12:00 – 13:30 Lunch午餐

Afternoon session:Moderator Prof. Henco Bekkering

下午場次:主持人Henco Bekkering教授

13:30 - 14:30

Keynote Speech.

Henk Ovink (Directeur visie ontwerp strategie, Ministry VROM / DGR)

- Randstad, 2040 towards a sustainable and competitive delta

講者:Henk Ovink(荷蘭之住宅空間規劃與環境部,初步策略執行長)

講題:荷蘭蘭得斯塔德區,2040年邁向可持續、有競爭力之三角洲

14:30 - 15:30

Keynote SpeechDr.

Thorsten Schütze-Water in the Dutch Randstad

講者:Thorsten Schütze博士

講題:荷蘭蘭得斯塔德區之水文

15:30 – 16:00 Tea break

16:00 – 16:45

Luis Chuang(DHV)-Caofeidian Coastal City

講者:Luis Chuang(DHV)

講題:曹妃甸海岸城市(河北省唐山市以南之島嶼)

16:45 – 17:30

D.J. Dick Kevalam(DHV)-Living with Water, Coastal and Urban

Development

講者:D.J. Dick Kevalam(DHV)

講題:與水共存,海岸與都市發展

17:30 – 18:00 Discussion座談

... Read more.

6/14 Day 2 議程

Morning session: Moderator Prof. John K.C. Liu

上午場次:主持人劉可強教授

09:00 – 09:45

Prof. Mao Qizhi -The water system and urban development,

case study in Beijing

講者:毛其智教授講題:水系統與都市發展之北京案例

##CONTINUE##

09:45– 10:30

Prof. Heng Chye Kiang-Water and Singapore: from scarcity to ABC

講者:王財強教授

講題:水與新加玻:從缺水到ABC(Water program)

10:30 – 11:00 Coffee break休息

11:00 – 11:45

Prof. Mooyoung Han-Hangang Renaissance Project in Seoul

講者:韓武榮教授

講題:首爾的漢江復興計畫

11:45 --12:30

Prof. Tsou Jin Yeu-Performance-based approach for sustainable urban

planning and design using PRD and HK as example

講者:鄒經宇教授

講題:採生產管理之效能取向的可持續都市規劃與設計-以香港為例

12:30 – 14:00 Lunch午餐

Afternoon session: Moderator Prof. Jürgen Rosemann

下午場次:主持人Jürgen Rosemann教授

14:00 – 15:00

Keynote Speech

Prof. Zhen Shiling - The Waterfront Regeneration and the Urban

Transformation in Shanghai

講者:鄭時齡教授

講題:上海的水岸城市再生與都市轉化

15:00 – 16:00

Keynote Speech

Prof. David Harvey-The Right to the City

講者: David Harvey教授

講題:到城市的權利

16:00 --16:30 Tea break午茶休息

16:30 – 17:15

Prof. Lee Hong-Yuan -Holistic approach of urban revitalization

-Taipei Experiences

講者:李鴻源教授

講題:城市再活化:台北縣經驗

17:15 – 18:00

Final discussion and conclusion 座談與結論

18:00 – 18:10

Closing (announcement of IFoU Annual Meeting 2008)

Vivienne C.Y. Wang (Director of IFoU)

閉幕式(國際城市論壇2008年會宣告事項)

王秋元(國際城市論壇執行長)

... Read more.

2008年6月8日

Bring water to Beijing-中國世紀工程:南水北調簡介

##CONTINUE##

檢視較大的地圖

↑"穿黃工程" 鄭州市以西30公里 孤柏山灣

南 水 北 調 工 程 的 由 來

1952年10月,毛澤東同志在聽取原黃河水利委員會主任王化雲同志關於引江濟黃的設想彙報時說:“南方水多,北方水少,如有可能,借點水來也是可以的。”從此,拉開了南水北調工程的大幕。

1959年2月,中科院、水電部在北京召開了“西部地區南水北調考察研究工作會議”,確定的南水北調指導方針是:“蓄調兼施,綜合利用,統籌兼顧,南北兩利,以有濟無,以多補少,使水盡其用,地盡其利。”

1978年9月,中共中央政治局常委陳雲就南水北調問題專門寫信給水電部部長錢正英,建議廣泛徵求意見,完善規劃方案,把南水北調工作做得更好。同年10月,水電部發出了《關於加強南水北調規劃工作的通知》。

1978年五屆全國人大一次會議上通過的《政府工作報告》中也正式提出:“興建把長江水引到黃河以北的南水北調工程”。

1979年12月,水電部正式成立了部屬的南水北調規劃辦公室,統籌領導協調全國的南水北調工作。

1987年7月,國家計委正式下達通知,決定將南水北調西線工程列入“七五”超前期工作專案。要求1988年底完成南水北調西線工程初步研究報告;1990年底,完成南水北調西線工程雅礱江調水線路的規劃研究報告;“八五”繼續完成通天河和大渡河調水線路的規劃研究工作,並於1995年完成南水北調西線工程規劃研究綜合報告。

1991年4月,七屆全國人大四次會議將“南水北調”列入“八五”計畫和十年規劃。

1992年10月,中國共產黨十四次代表大會把“南水北調”列入中國跨世紀的骨幹工程之一。

1995年12月,南水北調工程開始全面論證。

2000年6月5日,南水北調工程規劃有序展開,經過數十年研究,南水北調工程總體格局定為西、中、東三條線路,分別從長江流域上、中、下游調水。

相關網站:

- 中國南水北調工程網 http://www.nsbd.mwr.gov.cn/

- 中華人民共和國水利部 http://www.mwr.gov.cn/

講者簡介:李鴻源教授

台北縣副縣長、台大土木系教授

##CONTINUE##

學歷:美國愛荷華大學博士

專長:河川水力學、泥砂運動力學、流體力學

曾任:

美國愛荷華大學 水利研究所 博士後研究員

DOOLEY-JONES & ASSOCIATE WATER RESOURCE ENG. DEP. 資深工程師

國立台灣大學 土木工程學系 客座副教授

國立台灣大學 土木工程學系 副教授

個人網頁http://www.ce.ntu.edu.tw/~hydraulics/teacher/hylee.html... Read more.

「讓新加坡成為水與花園的城市」--ABC Waters Programme簡介

新加坡面積雖小,境內卻有一半以上的面積是河川集水區域,預計到2011年,積水區面積會增加到全國土地的三分之二,國家治理水域的策略更形迫切與重要。

新加坡水文圖

##CONTINUE##

新加坡的ABC Water Programme是一個永續的水資源管理策略,它由三個核心理念所構成:

ACTIVE:提供新的社區活動空間、讓人們更靠近水、發展人們對當地水域的認同。

BEAUTIFUL:將各地的水道與水塘以都市地景的視野作整體規劃、創造城市水域的新美學吸引力。

CLEAN:改善水質、加強水資源觀念教育、重建人與水的關係。

ABC Waters Programme是新加坡政府近年來大力推動的環境與水資源政策,並以此為原則,結合各領域專家,在新加坡各地的鄰水區域針對各地特色作出因地制宜的規劃。

資料來源:新加坡環境與水利用部門

http://www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/nbsap/nbsapcbw-seasi-01/other/nbsapcbw-seasi-01-sg-water-en.pdf... Read more.

講者簡介:Bernardo Secchi教授

professor of Urban planning at the Institute of Architecture, University of Venice (IUAV)

##CONTINUE##

Bernardo Secchi graduated in 1959 in civil engineering at the Milan Polytechnic under prof. Giovanni Muzio with a thesis on urbanistics. In 1960 he became the assistant of the same prof. Muzio, Chair of Urbanistics, Faculty of Engineering, Milan Polytechnic. During this time he was appointed a member the Scientific Comittee of the Intercommunal Plan for the Milan area and head of the technical office of the same plan. Following this he became Head of Research at the Lombard institute of Economic and Social Studies (Ises).

In 1966 he was appointed professor of Territorial Economy, first at the Faculty of Economics of Ancona, and following that, at the Venice University Institute of Architecture. At the same time he worked with prof. Giuseppe Samonà on the consultation draft for the plan for the Province of Trento and the plan for the Valle d'Aosta.

Since 1974 he has been a full professor of Urbanistics( Town planning and design); From 1974 to 1984 at the Milan Faculty of Architecture, where he was Principal from 1976 to 1982; and from 1984 at the Venice University Institute of Architecture degree course in Architecture. Since 1986 he has also taught at the "Ecole d'Architecture de Gènève". In the following years he held seminars and courses at the same institute, at the University of Leuven, at the Federal Polytechnic of Zurich, at the Paris Institute of Urbanism and at the Ecole d'Architecture de Rennes.

At the same time he was involved in drawing up the new general city plan of Madrid, the new town plan for Jesi (1984-1987), Siena (1986-1990), Abano (1991-1992) and, the plan for the old Town Centre of Ascoli Piceno (1989-1993). He has worked with Paola Viganò since 1990, producing the consultation draft of the territorial plan for La Spezia and the Val di Magra (1989-1993) and for the Province of Pescara, the new plan for Bergamo (1994), Prato (1996), Brescia, Pesaro, Narni and for the Salento region (Province of Lecce) in the South Italy.

He has designed public building quarters including the Plan for Economical and Popular Building at Vicenza, and was commissioned to draw up the consultation drafts of the recovery plan of the Sècheron industrial area at Geneva (1989), for the plan of Rovereto (1992); for the renovation plan of a small center close to Prato (Garduna-Jolo 1988-1992), a plan for the IP area of La Spezia; and he designed a carpark in a park in the 'area of Porta Torricella at Ascoli Piceno.

In 1990 he won the competition for planning Hoog Kortrijk (Belgium) having been invited to take part along with other European urbanists and architects; he drew up the consultation draft of the city of Kortrijk plan (1991) and in particular developed the projects of the Great Square and the new Cemetery of the selfsame town. Again with Paola Viganò he drew up the design of the public spaces along the Dijle river in Mechelen (2001,Belgium) and won (2002) the competition for a new design of Hoge Rielen (Belgium). As a planning consultant he won the Ecopolis competition for the project of a new city in Ukraine (group directed by Vittorio Gregotti, 1993). Working with others he won in 1993 the competition "Roma città del Tevere" (Rome, City on the Tiber), a project for work on the riverbank. With others he won the competition for the planning of the Airport zone (Rectangle d'or) of Geneva (1996). Since 1996 he has been "urbaniste conseil" for the "Etablissement public Euromediterranée" for the planning of the central and port areas of Marseilles. He has been consultant since 1996 to the Genoa Port Authorities working to produce the general plan for the port.

He was a founder member, and continues as a member, of the editorial body of the Urban and Regional Study Archives: and since 1982 he has been continuously working with the magazine Casabella and from 1984 to 1990 he directed Urbanistica. He has organised numerous planning competitions including "the Bicocca project", Milan; "Community buildings", Salerno and has been part of numerous jurys for architectural and urbanistic competitions (Milan, Bicocca; Antwerp, Staad aan de Stroom; Bologna: stazione centrale; Como: Ticos area; Roma, Borghetto Flaminio; Geneva, Palais des Nations; Lyon, Grand prix des formation, etc.).

資料來源:http://www.planum.net/topics/main/m-secchi-biogr.htm

最後點閱日2008年6月8日

講者簡介:鄭時齡教授

同濟大學建築與城市規劃學院教授

同濟大學建築與城市空間研究所所長

##CONTINUE##

1965年本科畢業於同濟大學建築學專業,1993年獲得同濟大學建築歷史與理論專業博士學位。曾任同濟大學建築城規學院院長、同濟大學副校長等職。

現任中國建築學會副理事長,上海建築學會理事長,國務院學科評議組成員,法國建築科學院院士。2001年當選為中國科學院院士。

鄭時齡教授在30多年的建築創作實踐中,致力於將設計與建築理論相結合,追求創作活動的學術價值;並將學術思想融於建築教學之中,形成自成一體的建築教學思想,建立了「建築的價值體系與符號體系」理論框架,奠定了建築批評學的基本理論長期從事理論研究、建築教學和建築創作活動,出版主要專著4部,譯著2部,在國內外發表學術論文50餘篇,設計作品35項。他的專著《建築理性論》和《建築批評學》建立了「建築的價值體系和符號體系」這一具有前沿性與開拓性的理論框架。後者以批判精神面向未來建築的發展,奠定了這門綜合學科的理論基礎,填補了該領域的空白,並應用該理論在上海建築的批評與建設實踐中起了重要的作用。其專著《上海近代建築風格》獲2000年上海市優秀圖書一等獎。

資料來源:同濟大學網頁http://www.tongji.edu.cn/tongjigailan/zhengshiling.asp

最後點閱日2008年6月8日

講者簡介:鄒經宇教授

香港中文大學太空及地球信息研究所副所長

香港中文大學中國城市住宅研究中心主任

香港中文大學建築系教授

1992年於香港中文大學創辦建築系之初,獲聘至香港中文大學任職迄今。

##CONTINUE##

協助建築學系建置虛擬現實實驗室及電腦實驗室,及發展設計計算學和電腦輔助設計、環境設計及建築空氣動力學等教學研究。並積極發展跨領域跨學科研究,與香港中文大學其他系所、國際和中華人民共和國、香港、臺灣地區的知名大學、研究單位和知名學者、城市規劃與建築設計與研究機構、香港及中華人民共和國相關政府規劃、建設管理部門及企業有廣泛的合作關係並開展相關研究,並與香港特區房屋署、中國城市規劃設計研究院等重要機構專門建立有密切的固定研究協作夥伴關係。

1998年於中華人民共和國建設部科技學術委員會支持下,於香港中文大學成立中國城市住宅研究中心。長期致力於通過設計與技術結合以促成高品質、經濟適用型的城市住宅研究,及城市可持續發展相關領域研究。

與中華人民共和國建設部科技委合作舉辦「中國城市住宅研討會」,自1998年迄今已經舉辦六屆,第七屆大會將於2008年9月在重慶召開,研討會結合了兩岸三地及國際學者的參與,各屆論文集已成為重要學術參考文獻。

資料來源:香港中文大學建築系網頁http://www.arch.cuhk.edu.hk/... Read more.

2008年6月7日

講者簡介:王財強教授

新加坡大學設計與環境學院建築學系教授。

##CONTINUE##

主要教學方向與研究領域:

建築與都市規劃、城市與建築史。

Academic/Professional Qualifications:

Architecte D.E.S.A (1983), Ecole Speciale d'Architecture, Paris, France

C.E.S (Amenagement Urbain)(1984) Ecole Nationale des Travaux Publics de l'Etat, Paris, France

PhD (1993), University of California, Berkeley, USA

Awards/Honours (Post-PhD):

Design consultant for Tianjin's Xiaobailou District Int'l Urban Design Competition--First Prize (2004)

Design consultant for Suzhou Graduate Campus City Int'l Urban Planning/Design Competition--First Prize (2002)

Outstanding University Researcher Award (1997)

Career History:

Architectural Assistant, Marzaki Consultancy Services, France (1982-83)

Senior Tutor (1986-93); Lecturer (1993-95); Senior Lecturer (1995-99); Associate Professor (1999-2003); Professor (2003-present), NUS

Administrative Leadership:

Head, Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment (2002-present)

Deputy Director, University Office of Research (2002-present)

Vice Dean (Academic), School of Design and Environment (2000-2002)

Professional/Consulting Activities:

URA Board Member (2002 to date)

Member of Advisory Board, Faculty of Architecture, Hong Kong University (2004 to date)

Associate Member, Singapore Institute of Architects (1994-Present)

Major Publications (Maximum of 3):

HENG Chye Kiang, "Learning from Carvajal, an Insignificant Alley" in Urban Design International. (2001) 6, 191-200.

HENG Chye Kiang (1999), Cities of Aristocrats and Bureaucrats. Univ of Hawaii Press and Singapore Univ Press.

HENG C K & Gan S M (1999), Multimedia Package on the Reconstruction of Tang Period Chang'an

資料來源:國立新加坡大學設計與環境學院網頁http://www.sde.nus.edu.sg/

最後點閱日2008年6月7日... Read more.

2008年6月5日

Prof. David Harvey's curriculum vitae

紐約城市大學研究生中心人類學博士學程特聘教授

Distinguished Professor of the Graduate Center, CUNY

專長學門(Specialized Field):

Cultural, Urbanization, environment, political economy, geography and social theory;

##CONTINUE##

榮譽及勛獎(Honor and Awards):

1989年獲瑞典人類學與地理學會Anders Retzius金質勛章;

1987-1993年牛津大學, Halford Mackinder地理學講座教授;

1995年獲英國皇家地理學會貢獻人(Patron’s)金質勛章;

1995年獲法國Vautrin Lud國際獎;

2002年獲皇家蘇格蘭地理學會百年獎(centenary medal);

2007年獲選為美國藝術與科學學院院士

著作(Publications):

Explanation in Geography (1969)

Social Justice and the City (1973)

The Limits to Capital (1982)

The Urbanization of Capital (1985)

Consciousness and the Urban Experience (1985)

The Condition of Postmodernity (1989)(有中譯)

The Urban Experience (1989)

Teresa Hayter, David Harvey (eds.), The Factory and the City: The Story of the Cowley Automobile Workers in Oxford (1994)

Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference (1996)

Megacities Lecture 4: Possible Urban Worlds, Twynstra Gudde Management Consultants, Amersfoort, The Netherlands, (2000)

Spaces of Hope (2000) (有中譯)

Spaces of Capital: Towards a Critical Geography (2001)

The New Imperialism (2003)

Paris, Capital of Modernity (2003) (有中譯)

A Brief History of Neoliberalism (2005)

Spaces of Global Capitalism: Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development (2006)

The Limits to Capital New Edition (2006)

Education(學歷):

B.A. (Hons) St Johns College, Cambridge, 1957

Ph.D. St Johns College, Cambridge, 1962

Career(經歷):

Post-doc, University of Uppsala, Sweden 1962-1963

Lecturer, Geography, University of Bristol, UK (1963-1969)

Associate Professor, Department of Geography and Environmental Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, (1969-1973)

Professor, Department of Geography and Environmental Engineering, Johns Hopkins University (1973-1987, and 1993-2001)

Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography, University of Oxford(1987-1993)

Distinguished Professor, Dept. of Anthropology, City University of New York (2001-present)

參考資料:

http://web.gc.cuny.edu/anthropology/fac_harvey.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Harvey_(geographer)

作為現代性的神話—創造性破壞(上):《巴黎,現代性之都》

作為現代性的神話—創造性破壞(下):《巴黎,現代性之都》

今日烏托邦 明日的現實- 訪David Harvey... Read more.

講者簡介:毛其智教授 Prof. Mao Qizhi

清華大學建築學院副院長

##CONTINUE##

主要教學科研方向和研究領域:

城市與區域規劃設計, 基礎設施規劃, 地理信息系統、遙感、虛擬現實技術在城鄉規劃中的應用。參與並主持聯合國地域開發中心、聯合國開發計劃署、 加拿大國際開發署,國家自然科學基金、建設部、教育部、北京市等多種科研項目,以及國內各地的城鄉規劃設計研究。

每年開設的研究生課程:

城市基礎設施與規劃、近現代城市規劃引論

自1985年起在北京清華大學建築學院任教,除此之外身兼多項學術機構職位:

世界人類聚居學會(WSE)副主席

中國建築學會國際合作工作委員會副主任

建設部城鄉規劃專家委員會委員

全國高等學校城市規劃專業指導委員會副主任委員

北京城市科學研究會副理事長兼歷史文化名城委員會主任

北京城市規劃學會新技術應用學術委員會副主任

中國地理信息系統協會理事

《地理信息世界》編委會委員

《城市發展研究》編委會委員

資料來源:北京清華大學網頁http://www.tsinghua.edu.cn/qhdwzy/index.jsp

最後點閱日2008年6月4日

2008年6月4日

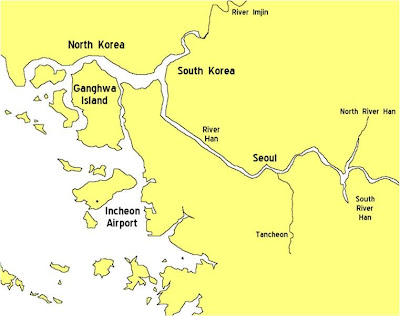

母親之河--首爾漢江新風貌

北漢江又名臨津江,是漢江的北支上流,源自北韓境內的金剛山; 南漢江源自大德山。兩江分別流經南北韓的江原道,然後於統一展望台附近合流,然後轉入京畿道。它把韓國首都首爾南北一分為二,然後再流入西海的江華灣出海。 在韓國人心目中,漢江是一條「母親之河」,與韓民族文化有密不可分的關係。

##CONTINUE##

根據首爾市公開的「漢江復興總體規劃」,要將漢江周邊8個地區建成為臨江新城,打通西海到漢江的水路,將如矣島和龍山建設成為國際船舶碼頭。

為了提高漢江的易接近性,首爾市政府將對漢江邊的景觀進行有體系的管理。與此同時,建設以漢江為中心的綠色生態網路,對漢江邊的混凝土堤岸進行拆除。該長期總體規劃是以持久性和連續性為前提的漢江發展計畫,歷經10個月才制定完畢。

首爾市將以以下8方面的內容為重點進行改造:

1. 以漢江為中心對城市的空間進行改造

2. 打造親水城(waterfront town)

3. 改善漢江邊的景觀

4. 構建通往西海的水運路線

5. 構建以漢江為中心的生態網路

6. 提高漢江的易接近性

7 .連接漢江邊的歷史文化資源

8 .建成不同主題的漢江公園

此外,為了方便市民們利用漢江邊的設施,使前往漢江的方式更加多樣化。強化與地鐵站和公共汽車站的連接,增建自行車道,並改善各條通路的環境和通行條件。與此同時,還將推行多處漢江公園主題化工程,並對漢江橋樑、橋墩、公園、建築物、擁壁等的晝夜景觀進行有體系的改造和管理。

資料來源:

首爾世界化中心http://global.seoul.go.kr/chinab/view/business/bus05_03.jsp

最後點閱日2008年6月4日

城市沙漠的綠色之心--荷蘭蘭德斯塔德區

##CONTINUE##

蘭斯塔德空間結構的形成主要與該地區的自然地理有關。該區以粘土和泥碳土為主,河川縱橫,儘管土地肥沃,人們卻難以進入與定居,早期的村落只能沿著河岸堤壩或小山丘發展。隨著大壩及水渠的建設,位於阿姆斯特河附近的阿姆斯特丹和位於鹿特河附近的鹿特丹等貿易城市形成了。由於這些城市之間的地段因地勢低窪而難以利用,城市開發與基礎設施建設都只能環繞綠心進行,一個獨特的空間形態就逐漸產生了。

保護綠心是荷蘭的國策。蘭斯塔德的經濟中心地位、快速城市化、土地資源稀少、人口增長及政策與管理方面的缺陷使綠心面臨用地競合、景觀被破壞、生態環境惡化等新的問題和壓力。荷蘭國家空間規劃通過建立區域性聯合機構、使空間規劃走向明確與具體、增強保護政策的彈性、制定自然生態政策等措施來保護綠心開放空間。

荷蘭國家城市政策由於近幾十年來的成功而備受國際讚譽,但其規劃的可接受程度與實施的效果遭到了部分專家的質疑。綠心政策在阻止蘭斯塔德朝中心開放空間發展方面的效果不佳,1970 年∼1990 年,綠心內的住宅增長速度竟超過了周邊城市內的住宅增長速度。1990 年,政府又允許高速鐵路線穿越綠心。綠心中有相當數量的開發項目與基礎設施建設,且綠心的人口密度高出全國平均水準。因此,綠心政策是否適宜就引起了爭議:有的專家認為,由於社會發展壓力和其他眾多不利因素,保持“綠心”的開放性並不現實,如住宅會以各種形式擠進綠心,如果對其進行全面圍堵肯定會導致失控;亦有專家認為,綠心是一種虛構的、憑空想像的概念,作為國家政策的依據並不夠充分。

資料來源:

大英百科全書,大英線上繁體中文版,最後點閱日:2008年6月1日 http://wordpedia.eb.com/tbol/article?i=062427

96年度國土規劃總顧問《技術報告》